Wood

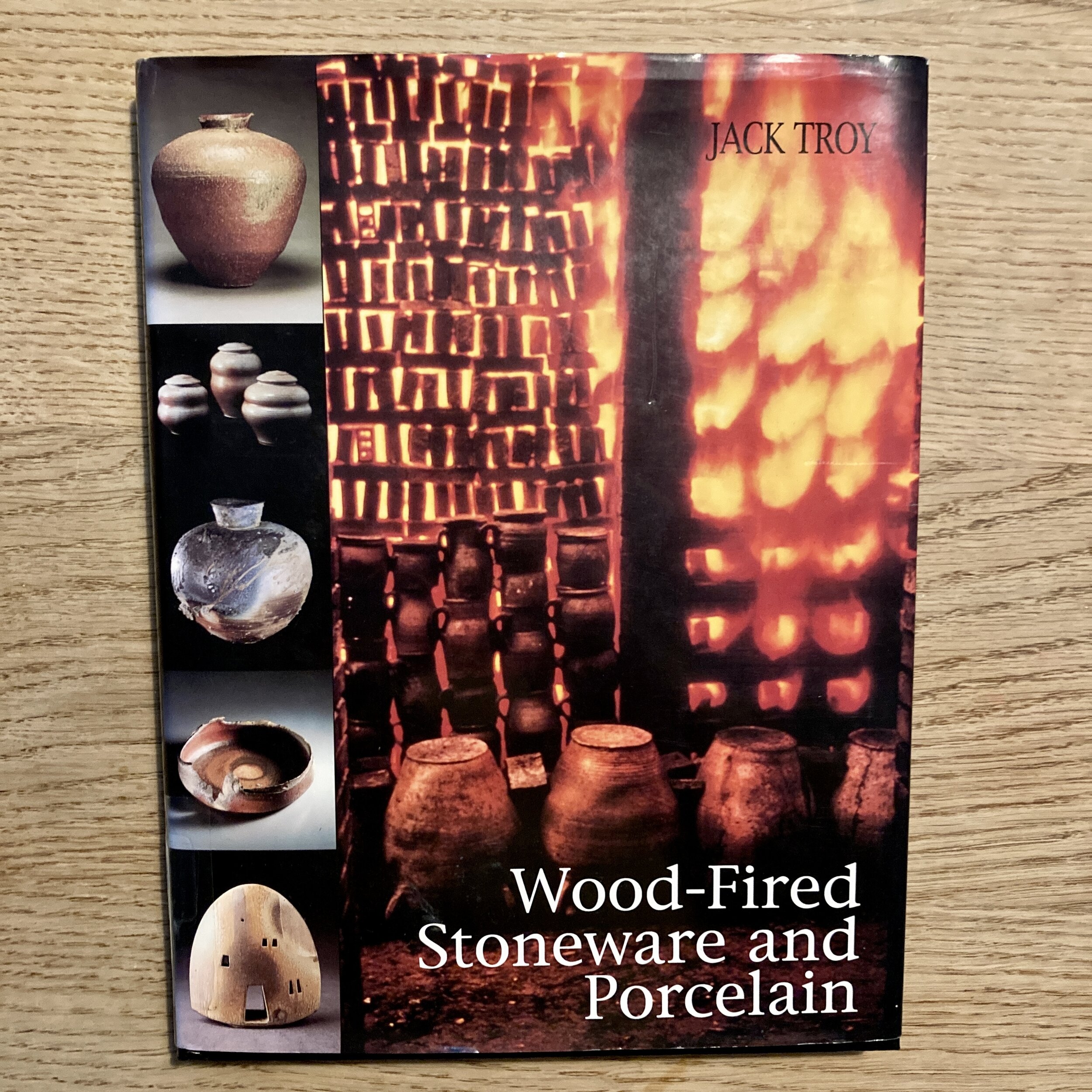

My Dad, along with a career in Information Systems, and thirst for windsurfing, was a keen cabinet-maker. Despite dozens of evocative memories, of the smell of pitch-pine, and the papery curls from a sharp hand plane littering the garage floor, or the almost abrasive quality of oak dust, I had not given the technical qualities of wood much thought. In my mind, wood (at least for this project) was pretty much wood. - Of course I knew that moisture content and the size of the fuel would be important, and I suppose that I also knew that some woods would burn hotter than others… And then I read Jack Troy’s ‘Wood-fired Stoneware and Porcelain’ and I began to see just how little I knew about wood.

While I am certainly not in the privileged position to be able to pick and choose my types of wood fuel, I can begin to make some decisions. Where possible I will fire with local trees, not lumber or waste from local sawmills, but branches from trees felled within walking distance of the kiln. The calorific content of these trees may be a bit of a lottery but, most importantly, it will not be just heartwood. The sapwood and bark (and all that juicy lichen) are the most mineral rich parts of the tree, and will carry those precious “solubles” directly onto the ware. It should, I hope, promote ‘flashing’ and impart something authentic of this place to the work.

When a tree is felled, to manage the local woodland, it’s surprisingly quick and enjoyable to strip the thinner branches (those measuring about 1inch thick are ideal) with a bill-hook. Later, I cut these into 50cm lengths and stack then in the kiln shed for drying. I’m looking for around 18 to 20% moisture content, and a moisture meter from my own woodworking days, should come in handy here.